By : Brian Yap

Email to friend  Print article

Print article

LANGUAGE is of course one of the main pillars of any culture, a defining characteristic of any race.

Considering that Malaysia is a former British colony that is also home to three major and countless other races, it is not surprising that a plethora of languages and their dialects are used here.

What’s more, with so many foreign workers and international students in our urban centres these days, I almost have to think twice before opening my mouth — should I use Bahasa Malaysia, English, Cantonese or Mandarin?

Surprisingly, English is the language I feel most comfortable and confident using. I read, write, think and probably dream in the language. I say surprising because I never went to an English-medium school — aside from international schools, there was simply no such option available during my time. So for all 11 years of my primary and secondary education, I learned all subjects — except English, of course — in the national language.

At the same time, I had private Mandarin lessons when I was younger, but it never got very far. After quite a few years, the Taiwanese lady who taught me gave up in exasperation at my non-progress. Today, I can speak little more than casual Mandarin, and write little more than the three characters that make up my name.

It’s ironic that despite being taught Bahasa Malaysia and Mandarin, English would be the language I’m most proficient in. I suspect it had a lot to do with what my pop culture references were — meaning the books and magazines I read, the TV programmes I watched and the pop stars I looked up to.

In recent years, many have lamented the decline of the English language in Malaysia. The previous administration even tried to address this by making schools teach Maths and Science in English.

While it’s hard to argue that the learning of languages, especially one that is practically universal like English, is beneficial and crucial, I feel its importance is often overrated.

More than teaching Maths and Science in English, schools need to improve the standard of both subjects instead. If improving English is important, then it could be addressed with improving the quality and quantity of lessons instead.

The decision in 2003 to teach Maths and Science in English was a controversial one. The vernacular schools felt that it was another way for the government to exert control over them, while rural schools were worried about how well prepared the teachers would be, and if their students’ performance in Maths and Science subjects would decline because of the additional burden of learning an unfamiliar language.

It has now been all but confirmed that the sudden switch wasn’t the best of ideas. The initial plan was to have Year Six pupils answer their Mathematics and Science papers completely in English from next year.

But now, examinations in English for Maths and Science subjects will continue to remain optional.

Of course, it’s not quite a reversal of the decision, but there are obviously difficulties and doubts, which unfortunately leaves the education system in a state of a limbo. All that to improve the standard of English in this country.

For all the worries about our declining standard in English, we probably do have a better command of the language than many other countries in our region, generally speaking.

I’m confident that Malaysians on average speak better English than the Thais and Indonesians, for instance. Economically developed Asian countries like Japan, Korea and, now, China, have not been particularly disadvantaged by their lack of English skills, because they have other more important things to offer — a strong work ethic, a thirst for knowledge and progress, and a quality education that provides solid foundation. These are areas Malaysia needs to be more concerned about than merely mastering English.

English-speaking Malaysians often make light of others who cannot speak the language well, as if it were the only measure of intelligence and modernity.

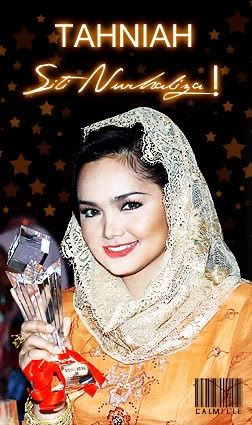

For instance, pop star Siti Nurhaliza has been ridiculed by some for her inability to speak in English, even when she is interacting with foreign media. The few times she’s tried, some even pointed out her mispronounced words. But why should she care? She is the biggest pop star in Malaysia, with fans all over the region.

Smug English-speaking Malaysians can make fun of her all they want, but none of them will ever sell as many records as she does, nor entertain as many people.

No doubt, it would be ideal if all Malaysians had an excellent command of English. That would surely be an advantage in a time when much of the world’s communication is conducted in that language. The Internet, for instance, is overwhelmingly dominated by content in English.

But it’s silly to think that our progress depends solely on our ability to master the language. We need Malaysians to be more hardworking, intelligent, well-read and open-minded, and we can be all of those things in whatever language we choose.

source: The New Straits Times